What is it?

- The Mauryan Empire is considered to have been founded by Chandragupta Maurya (321-297 BCE). Chandragupta assembled an army and defeated the Nanda empire in Magadha, present-day eastern India, creating the Mauryan Empire.

- After becoming king, Chandragupta expanded his territory by force and alliances.

- Kautilya, Chandragupta’s chief minister, advised him and contributed to the empire’s legacy.

- The Mauryan empire was a turning point in Indian history.

- For the first time in Indian history, a substantial area of the subcontinent was dominated by a single dominant authority, spanning up to the far northwest.

Administration of the Mauryan Period

- Monarchical: The empire was ruled by a king or monarch, with the first emperor being Chandragupta Maurya. His grandson, Ashoka, is often recognized as one of the Mauryan Empire’s finest emperors.

- Provincial Administration: The empire was split into provinces or administrative entities known as ‘Janapadas’ or ‘Pradeshas’. For effective government, these provinces were further subdivided into districts.

- Capital: The Mauryan Empire’s capital was initially at Pataliputra (modern-day Patna in Bihar, India). It served as a political and administrative center and was ideally placed along the Ganges River.

- Ministers: The monarch was assisted by a council of ministers who advised him on a variety of issues. The chief minister, also known as the ‘Mahamantri’, played a key role in the administrative structure.

- System of Taxation: The Mauryan Empire had a well-organized taxing system. Land revenue was a significant source of income, and taxes were levied in kind or as a fixed percentage of agricultural produce.

- Administration of the Military: The Mauryan Empire had a well-organized military force. The emperor maintained a large standing army composed of infantry, cavalry, and elephants. The military was critical to the empire’s survival and expansion.

Society of the Mauryan Empire

- Varna System: The Varna system affected Mauryan civilization, which classified individuals into four major varnas or classes: Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (labourers and service providers).

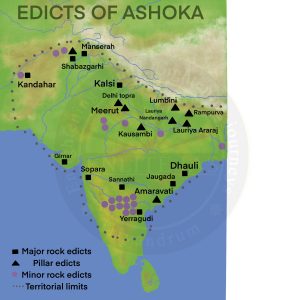

- The Dhamma of Ashoka: During the reign of Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire saw the spread of Buddhism through the emperor’s embrace of Dhamma precepts. Ashoka’s inscriptions and edicts emphasised ethical and moral behaviour, nonviolence, tolerance, and compassion. This had a tremendous impact on the social fabric of the time.

- City Centres: The Mauryan Empire had thriving urban centres, with Pataliputra serving as a renowned capital. Urbanisation resulted in increased trade, commerce, and a more complicated social structure.

- Economic Classes: Economic classes in society included affluent landowners, traders, artisans, and labourers. Land ownership and agriculture were important components of the economic framework.

- Caste System: While the Varna system defined broad classes, the caste system further divided people based on occupation, birth, and social position. Over time, the caste system became more strict, impacting social interactions and mobility.

- Women’s Roles: Women’s roles in Mauryan society varied depending on their social and economic standing. Women from higher social levels frequently had more freedom and participated in social and religious activities. However, the society was mainly patriarchal, and women’s roles were largely confined to home responsibilities.

- Religious Diversity: The religious variety of the Mauryan Empire was notable. While Vedic customs and Brahmanical practices were popular, Buddhism gained imperial backing under Ashoka. There were also adherents of various religious and philosophical systems.

- Slavery and servitude: Slavery was prevalent in the Mauryan civilization, and slaves were frequently used for labour-intensive activities. Additionally, servitude was common, with people serving others in various roles.

- Art and Culture: The Mauryan period saw tremendous advances in art and culture. For example, Ashoka’s pillars and rock edicts are noteworthy for their inscriptions and artistic renderings. The Mauryan period established the groundwork for later advances in Indian art and architecture.

Economy of the Mauryan Period

- The tax was collected in both cash and in kind.

- Rajukka measured the property.

- Tax-free settlements were referred to as Pariharaka, while tax-free land was referred to as Udwalik or Parihar. There was also the Pranay tax, which was a type of emergency tax.

- The state regulated all economic operations, including irrigation (Setubandha) and water taxation.

- The Mauryas’ imperial currency was punch-marked silver coins with the insignia of the peacock, the hill, and the crescent, known as pana.

- The token money was copper Masika, and quarter pieces of masika were known as kakini.

- The suvarnadhyaksa, laksanadhyaksa, and rupadarshaka are state officers in charge of currency, according to Kautilya.

- Horses, gold, glass, linen, and other items were the major imports.

Reasons for Decline of the Mauryan Empire

- Weak Successors: Following Ashoka’s death, the Mauryan Empire was ruled by a succession of weak and ineffective kings. These emperors could not sustain the empire’s unity and stability, so the empire began to dissolve.

- Administration Weakness: The Mauryan Empire’s size caused administration issues. Managing such a vast country became increasingly difficult as the empire grew. The deterioration was exacerbated by a lack of adequate administrative systems and an inability to address local issues efficiently.

- Brahmanical Reaction: Asoka forbade the killing of animals and birds and mocked needless female ceremonies. This naturally had an impact on the Brahmanas’ revenue. The Brahmanas suffered greatly as a result of Buddhism’s and Asoka’s anti-sacrifice stance, and they formed a dislike for him.

- Some of the new kingdoms that developed on the ruins of the Maurya empire, such as the Sungas and the Kanvas, were controlled by Brahmanas. Asoka ignored the Vedic sacrifices, which were done by these Brahmana dynasties.

- Financial Strain: Keeping a large standing army and Ashoka’s ambitious projects and welfare programs imposed a tremendous financial weight on the empire. Economic issues resulted from the financial strain, and the state struggled to earn enough cash to support its activities.

- Invasion and External Threats: The Mauryan Empire’s northwest boundary was constantly threatened by external invaders, particularly the Greek successors to Alexander the Great. External challenges to the Mauryan Empire were posed by the invasions of the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms, as well as the emergence of other regional powers.